I am taking this STATE-80 course from Harvard Extension School. This course teaches commonly used distributions and probability theory. The instructor Hatch is a really good teacher and he uses simulation for all the demonstrations along with the formulas.

In week 6, we revisited the Monty Hall problem which we played on the first day of class.

If you have not heard about it, I quoted from the wiki:

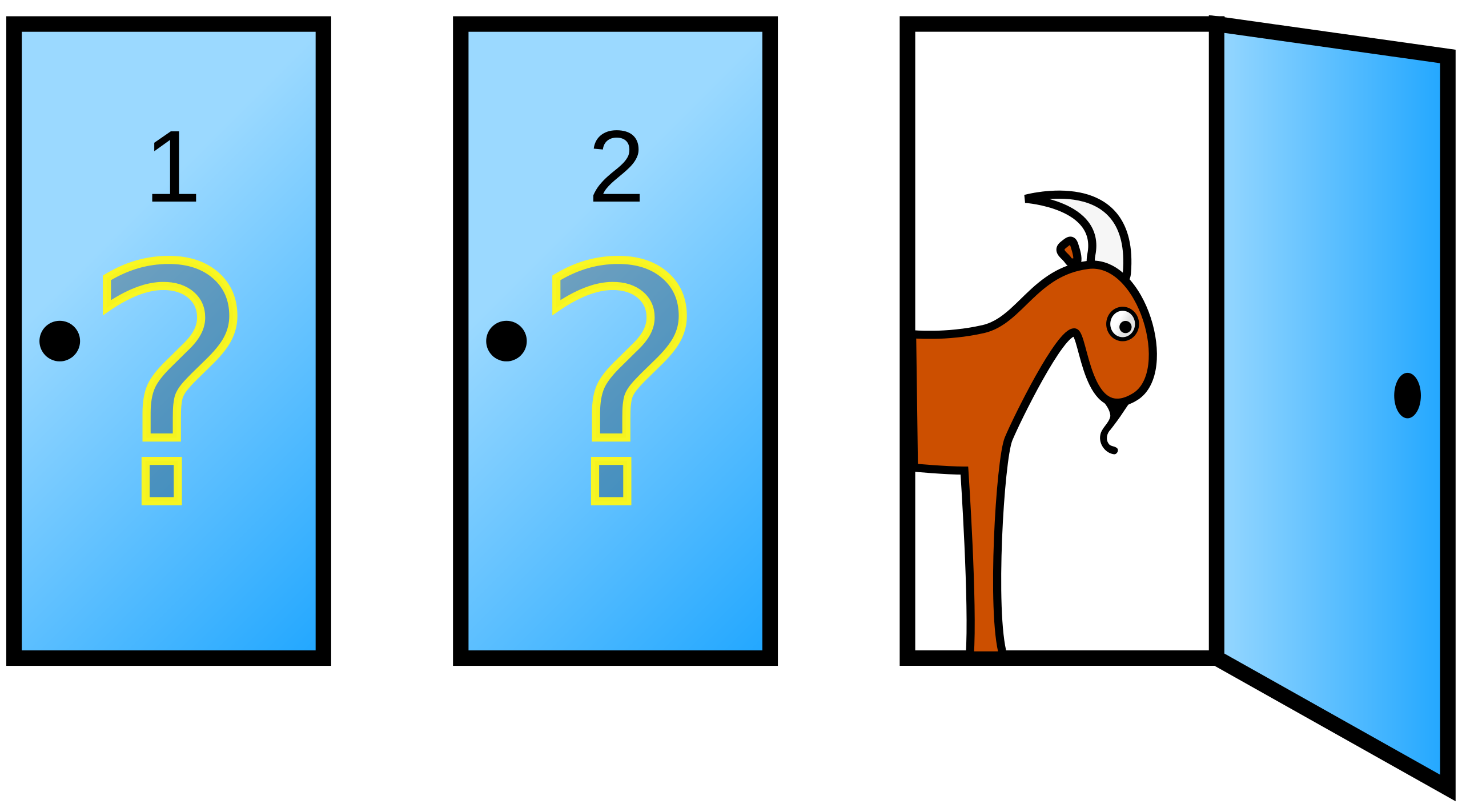

Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?

The answer is that it is to your advantage to switch the door. The probability of switching the door and get the car is \(2/3\) and the probability of not switching is \(1/3\).

Why if I switch I have a better chance to win the car? If the host opened a door with a goat, the car is behind the door of what I have chosen and the one I have not. Is not it 50% of chance to win the car whether I switch or not? It is so counter-intuitive that even Paul Erdős did not get it at first.

Let’s tackle it by simulation first and then I will give the formulas to deduce the result.

The code was copied from Hatch’s lecture notes. The variable names are clearly given and the comments also help you understand the code.

set.seed(123)

number.of.goats <- 2

number.of.cars <- 1

cars.goats.vector <-

c(

rep( "Goat", number.of.goats ),

rep( "Car", number.of.cars )

)

total.doors <-

number.of.goats + number.of.cars

door.vector <- 1:total.doors

number.of.replications <- 10000

outcome.vector <- logical( number.of.replications )

for( replication.index in 1:number.of.replications ) {

# First, we'll mix up the cars and goats

# behind the doors

random.cars.goats.vector <-

sample( cars.goats.vector )

# Next, let's figure out which doors have

# a goat behind them

goat.doors.vector <-

which( random.cars.goats.vector == "Goat" )

# Now the contestant makes the initial pick

initial.door.pick <-

sample(

door.vector,

size = 1

)

# The game show host determines which doors

# can be opened:

possible.to.open.doors.vector <-

setdiff(

goat.doors.vector,

initial.door.pick

)

if( length( possible.to.open.doors.vector ) == 1 ) {

open.door <- possible.to.open.doors.vector

} else {

open.door <-

sample(

possible.to.open.doors.vector,

size = 1

)

}

possible.final.door.vector <-

setdiff(

door.vector,

c( initial.door.pick, open.door )

)

if( length( possible.final.door.vector ) == 1 ) {

final.door.pick <- possible.final.door.vector

} else {

final.door.pick <-

sample(

possible.final.door.vector,

size = 1

)

}

outcome.vector[ replication.index ] <-

random.cars.goats.vector[ final.door.pick ] == "Car"

}Now, let’s check how many times one wins car:

cat( "Sample mean of outcome vector:",

round( mean( outcome.vector ), 5 ) )## Sample mean of outcome vector: 0.6705Is it surprising?! Let me explain in plain words:

Let’s focus on the strategy of always switching the door after the host opens a door.

If initially you picked a door behind which there is a car, the host opened a door (from either one) with goat, and you switch. The probability of getting the car is \(0\). You had the car behind your initial pick! If you switch, you get the goat.

If initially you picked a door behind which there is a goat, the host had to open the other door with goat, and you switch. The probability of getting the car is \(1\), because the host has leaked the information that the car is in the other door that you are going to switch to.

The probability of picking a door that a car behind the door for your initial pick is \(1/3\) (from 1, your chance is 0 to win the car). The probability of picking a door that a goat is behind the door for your initial pick is \(2/3\) (from 2, your chance is 1 to win the car). So in the long run, you have \(2/3\) chance to win the car.

Calculate by formulas

The trick to using conditional probabilities is to pick the right event to condition on. For the Monty Hall problem, we will condition on the event that Marie selects the door with the car behind it as her initial choice, and we’ll denote this event \(A\). Then the event \(A^c\) is that Marie does not select the car door as her initial choice, but instead selects a door with a goat behind it. Also, let \(B\) denote the event the event that Marie wins the car in the end. Now suppose Marie adopts the strategy of accepting the offer to change her initial selection after seeing another door opened with a goat behind it.

As I mentioned above:

\[ \Pr(B\ |\ A)\ =\ 0 \]

\[ \Pr(B\ |\ A^c)\ =\ 1 \] What’s the probability that Marie will initially select the door with the car behind it? It’s just 1/3. So we have: \[ \Pr(A)\ =\ 1/3 \] Then by the complement trick, we have: \[ \Pr(A^c)\ =\ 1 - \Pr(A)\ =\ 2/3 \] Now we can use the Law of Total Probability: \[ \Pr(B)\ =\ \Pr(B\ |\ A) \cdot \Pr(A) + \Pr(B\ |\ A^c) \cdot \Pr(A^c) \]

Substituting, we obtain: \[ \Pr(B)\ =\ \left ( 0 \cdot \frac{1}{3} \right ) + \left ( 1 \cdot \frac{2}{3} \right )\ =\ \frac{2}{3} \]

Monty Hall with more doors

Let’s try a Monty hall game with 4 doors behind which are 1 car and 3 goats. Just change

number.of.goats <- 3

number.of.cars <- 1You will get around \(3/8\).

With 4 doors, if you initially select a door with a goat, the host opens a door with goat, you will be leaving two doors: one with goat and the other one with car. So you will have \(1/2\) chance to win the car.

\[ \Pr(B)\ =\ \left ( 0 \cdot \frac{1}{4} \right ) + \left ( 1/2 \cdot \frac{3}{4} \right )\ =\ \frac{3}{8} \] It is always to your advantage to switch the door because the host has leaked information about the car :)

Simulation is a very good tool to teach statistic concept and especially for the non-intuitive ones.